Let me start with some basic questions that we need to ask ourselves: Why do most of our modern living and work environments make us exhausted and dispirited? Why do most of these environments tend to become life-sapping spaces rather than life-renewing ones? In spite of having good material specifications, excellent technological support in terms of lighting, climate control, equipment and other facilities, what makes these spaces lifeless?

All the measurable three-dimensional prerequisites for a good working environment seem to be in order. What I find amiss is the hidden, immeasurable dimension—a dimension that helps integrate the individual with the wholeness of life, that which exalts his own worth and supports the regeneration of his body and soul. We may call this the spirit dimension and ask: Why has our contemporary space failed to include this vital dimension in its multifarious vocabulary?

Let us begin with a quick look at our contemporary values and the quality of spaces created. This might reveal what may be ailing us and our environment today. Over-dependence on technology reduces the natural, pluralistic diversity and spontaneity to monotonous, predictable repetitiveness. This numbs our aesthetic appreciation and sensitivity. When short-sighted commercial goals are pursued, superficial gloss and attractive quick-appeal wrapping becomes more important than the inner content. Alienation from the direct, natural, real experience is further heightened because of indulgence in packaged artificial reality on television, computers and sense simulators. This is accompanied by an excessive use of synthetic materials, plastic grass, nylon flowers and artificial climate control.

A self-centred, greedy, consumption-oriented lifestyle, with undue importance attached to economic gain and security, leads to an over-cluttered way of life. Excessive consumption leads to wastage and the concept of disposability. Stealthily, this idea of disposing and dispensability has also crept into our human relationships. Today’s insular, segregated spaces have taken us further away from our fellow humans, and brought about our alienation from the healing and rejuvenating powers of nature. The solace and mental comfort derived from healthy interactive human relationships is missing. The adoption of high speed as a part of our daily lives—speedy transportation, speedy work output, speedy cooking, fast encounters—has not only changed our perception of time, but is also contributing to the deteriorating quality of our lives. Our inner psychological space experiences a cluttered confusion—a reflection of the chaotic clutter and information overload of our outer physical space.

All this tends to fragment the wholeness and unity of life. Whatever country, race, or religion we may belong to, we have all been experiencing the above phenomena. The issue is, are we going to continue in the future on the same path that we are on now, or could we pause and re-examine our parameters and priorities in life? It is definitely possible to pause and change course towards a richer and a more harmonious life.

Our concern as architects ought to be this: Can our designs enrich our human spirit or would they further contribute to the growing poverty of this human spirit?

What is this spirit and how does it relate with spirituality? To me, spirituality is the awakening of consciousness from self-centredness towards universal totality. In simple words, it is to relate and belong to this fascinatingly interconnected web of life, to feel like an integral part of this cosmic reality.

Can we integrate our small lives with Life itself and harmonize with it? Then a feeling of empathy for everyone and everything around us would unfold beautifully within us.

Why do ‘I’ feel satiated when my plants are watered after a long dry spell?

Why is it that ‘I’ feel free and happy when our dog is untied?

What makes ‘me’ bubble within at the sight of a bubbling, frothing stream or waterfall?

Why does a feeling of weightlessness engulf ‘me’ at the sight of that bird’s lovely flight?

Why do ‘I’ feel cleansed, refreshed in a beautiful, clean environment?

Why is it that ‘I’ feel balanced and harmonious within in a well-designed space?

Could our spaces too be designed in such a way as to give a glimpse of this universal totality? Could they relate to their surroundings and integrate with them? Could they not include the sky, the hills, the birds and the trees as a part of their space-forming vocabulary?

As designers, we need to work with a child-like spontaneity that comes from the absence of conditioning. This pen is not just a pen for a child; it can transform into a plane or a train, a sword or a stick, a lamp post or an injection syringe. We tend to brand an object and thereby miss all the potential multiple possibilities that it offers. We need the courage to create unique and pathbreaking designs.

Unfolding the spirit involves the creation of a self-organizing dynamic order in the working together of the implicate and the explicate. It also implies our shift from the measurable objective consciousness to the immeasurable subjective consciousness, while functioning simultaneously at multiple levels. Could our spaces be designed in such a way as to give a glimpse of this universal totality? Could they relate to their multiple contexts, grow out of them and integrate with them?

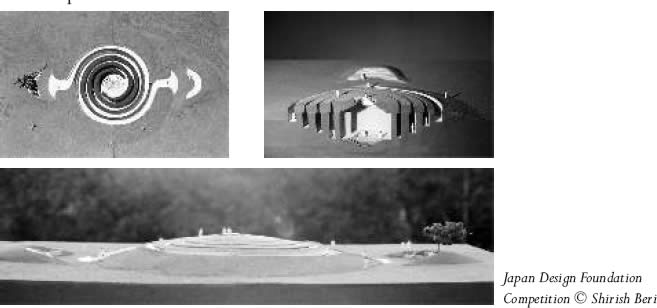

In the Japan Design Foundation’s International Design Competition, with the theme In Quest of Spiritual Comfort and Mental Relaxation, our entry was conceived as the state of dynamic balance between the introvert introspective movement and the extrovert outward-bound movement. The changes in the human mind are brought about by the gradual change in the quality of space that it experiences.

The spiritual happening

Could our space designs act as an interface between the dynamic forces seeking expression from within and those coming from without? Can the inner space within our consciousness harmonize with the outer space that we create?

Instead of just responding to the measurable rationale of the clients’ brief with a matter-of-fact objective consciousness, can we expand upon the brief and then design with a more value-based subjective consciousness? Can our design include both the measurable and immeasurable elements of life? For me, the subjective attitudes that shape a design are far more important than mere utilitarian requirements. These concepts and attitudes are what add life and spirit to the functional spaces, e.g. the step wells of the past as compared to the bore wells of today, or the old well-crafted food granaries compared to the shoddy, leaking godowns of today.

As they say, the house is made up of measurable walls, roof, floor, doors and windows, but the essence of the house lies in its emptiness, the quality of its immeasurable hollow space.

In South India, before work on a new house is started, a ceremony called garbhanyasam is performed, which means the impregnation of space for the creation of a building. This is a beautiful concept. An empty hollow copper vessel symbolizing space is held in an inclined position and seeds of five different kinds of grain, symbolizing external energies and resources, are thrown inside as an act of impregnation. Space is considered as something living.

In India, the lady of the house draws rangoli designs outside the front door every morning with coloured powders, to welcome the new day, or a guest, thereby starting the day with a creative activity. This activity recognizes the importance of space (by decorating it) and of time (by conscious awareness of a new day).

Spaces that are in touch with nature and its forces have been proved to have a rejuvenating effect on our body and soul. Can our designs act as a catalyst in bringing us closer to nature and to our inner spirit? Can the manmade and the natural be integrated so that a symbiotic relationship develops between the two? Then, sustainable designs that respect the spirit of this earth would spontaneously happen, and spaces can embody a healing quality.

A few months after a group of primary school students shifted into their new campus, which was designed around a tree, the teachers and matrons told me that the students had been less violent and destructive. They now appeared more joyous and creative. On being asked to write an essay on My Best Friend, many students wrote about this tree. The trees in my farmhouse and beach house have almost become like family members, whom I wish on arriving and bid goodbye while leaving. The rain falling in the courtyard has become one’s sibling.

Children are more sensitive to space and nature. I remember an incident at my friend’s place. We were sitting inside the hall. From the doorway, I could see my friend’s three-year-old daughter swaying harmoniously on the terrace. I became curious. I went to her and asked her what she was doing. She said, ‘Don’t you feel this breeze blowing here? I am swaying with it, like those branches and the leaves of that tree.’ Now, isn’t that wonderful?

Spirituality is to be connected, connecting to others as an extension of oneself. Can our designs contribute to the universal values of communicating, sharing, caring (not only with fellow humans, but with everything) by designing appropriate interactive spaces?

Spirituality is not an end product but a continuous, flexible, proactive, living process of evolution and growth. Kahlil Gibran gives a beautiful simile for how a house should shelter its inmates—not like a deadpan glistening bandage film that covers a wound, but like our living eyelid that shelters and covers the eye. This example implies a live process—with flexibility, manoeuvrability and adsorption. Can our spaces display this flexibility to grow, evolve, change and adapt? Could we design dynamic spaces that proactively adapt themselves to changing needs?

With true spirituality, there comes simplicity—a simplicity in spite of the diversity, plurality and complexity, a simplicity that has the presence of the essence and the absence of redundancy. Can our designs shed the redundant to reach a level of simplicity that is potent and strong by itself?

With spirituality comes honesty. There is no place for hypocrisy to disguise any reality. To overcome the casualness and the stylized fads and imitativeness that have crept into our designs, we really need to have silence, to pause and to re-examine our premises, understandings, values and attitudes, and translate them into the spatial language.

Can we create holistic, value-based designs leading to an architecture of belonging, of caring; an architecture of honesty, spontaneity and simplicity?

Ultimately, it is the kind of Life that we understand and live that finds expression in our work and behaviour. In order to bring about this renaissance in our designs for outer spaces, a renaissance has to happen in our inner mind. Only then will our designs breathe life into spaces. Instead of becoming energy-sapping, dispirited spaces, they would become spirited spaces that rejuvenate us, that delightfully affirm life, to bring joy and beauty in our lives.

May our architecture celebrate Life!